Home-sickness: Soviet forced laborers under the Nazis

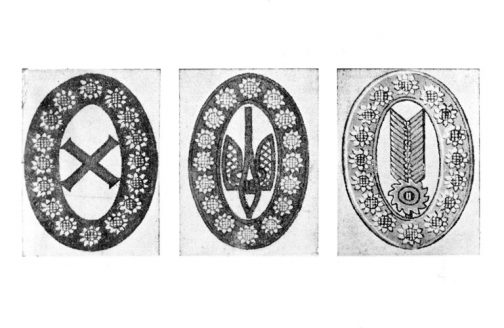

In 1944, the Nazis introduced so-called Volkstumabzeichen, or ethnicity badges, for forced laborers from Russia, Ukraine and Belarus (l. to r.).

In 1944, the Nazis introduced so-called Volkstumabzeichen, or ethnicity badges, for forced laborers from Russia, Ukraine and Belarus (l. to r.).Credit: picture alliance / ZB

We worked 12 hours every day,” recalls Larissa Shvydchenko. “After the night shifts, you just went back to your bunk and collapsed. Even when they shouted ‘There’s food, get up!’ you simply could not open your eyes.” Pavel Mikhailov writes, “We were nothing but skin and bones. We weren’t even people anymore, just mummies. No idea how we managed to stay on our feet. It was only because we were young that we survived.”

These are just a few examples of the hundreds of thousands of memories held by Soviet citizens forced to do labor in Germany during World War II. Beginning in the spring of 1942, nearly three million men and women were rounded up under threat of violence and other forms of retaliation in areas of the Soviet Union occupied by the Wehrmacht. The average age of the deportees was 20, but many were substantially younger, at just 15 or 16.

Of the 11 million slave laborers the Nazis rounded up to work in Germany, it was Soviet citizens – whom Nazi bureaucrats lumped together with other Eastern and Central European captives and referred to as Ostarbeiter – that were by far the largest single group. They were also treated with particular brutality; in the Nazis’ depraved hierarchy of nationalities, Ostarbeiter occupied the bottom rung.

In West Germany, historical interest in the fates of Soviet forced laborers, along with the idea of compensating these individuals for their suffering, first arose in the late 1980s. In the Soviet Union, too, the slave laborers’ stories were silenced for decades. Under Stalin, they were even denounced as traitors or collaborators. Only in the 1980s under Gorbachev and his policy of Glasnost, or openness, did many surviving forced laborers finally share their experiences.

A civil-rights society called Memorial, founded in Moscow in 1989 to shine light on Stalinist injustices, joined forces with the Heinrich Böll Foundation in Germany to focus on Nazi-era slave labor. It received a boost from a misleading newspaper report published across most of the USSR in April 1990, which claimed that anyone who wrote in to report their experiences could count on a pension from Germany. Almost immediately, Memorial received more than 400,000 letters.

These letters and many resulting interviews with slave labor survivors constitute a vast archive of the history of the Ostarbeiter in wartime Germany. Letters, postcards, photos and other documents unveil a panoramic window onto what these men and women were forced to endure so far from home. In 2017, a team of Russian historians published a documentary volume of the many memory fragments yielded by correspondences and interviews. That volume has now been published in German translation.

Rather than tracing the fates of individual persons, the book arranges fragments of recollections into thematic groups, beginning with the years before and during deportation to Germany. The great focus, however, is on accounts of living and working in Germany.

There are two key motifs that emerge time and again in these recollections: the brutality of the work and the constant hunger felt by the workers. It could make a huge difference, however, whether an Ostarbeiter worked for a major arms producer in a city or on a rural farm.

Alongside exhaustion and hunger, people felt lost and longed for their homes. “A foreign land, a foreign language and foreign customs. Some girls were only 13 or 14. They had it especially hard,” wrote Antonia Maxina. As Vadim Novgorodov recalled, “we did not really believe we would ever return home. We wanted to go back; we missed our families. It was hard to accept that we were no longer free.”

Despite their suffering, many forced laborers had nuanced memories of Germany and the Germans. Gestures of sympathy were very clearly recognized. Tatiana Veselovskaya recalls: “When I came back and opened my drawer, there was always some buttered bread and something else inside. Whoever it was who put it in there, I don’t know. The Germans were afraid of one another.” And Nadyezhda Bulava: “You know, I also met completely normal Germans. There were good people, including some who helped us. But most were fascists.”

For nearly all of these individuals, returning home became yet another bitter experience, as they were often treated with distrust and suspicion. “We noticed immediately: We were aliens, second-class. We could not be trusted. We have to be vetted, re-vetted, and vetted again,” recalls Zoya Yeliseyeva. “We were all interrogated: When did we leave where, with whom, who else was there, where were you over there, what did you do there, when did you return, who set you free?”

Some forced laborers were rewarded for their time in Germany with additional years in Soviet prison camps. Or they were openly discriminated against, as Valentina Yanovskaya recalls: “Whenever I tried to find work, the first question was always: Where was I during the war? In the occupied territory or evacuated? And then I had to listen to things so horrible that I didn’t want to live any more. How many times have I regretted having ever returned home?”

Klaus Grimberg

is a freelance journalist based in Berlin.